Table of contents

Open Table of contents

- Personal account

- Training Without Competing: Exercise as Nervous System Literacy

- The Nervous System Is Always Listening

- From Recognition to Understanding

- Exercise as Infrastructure, Not as a Scorecard

- The Missing Piece: Parasympathetic Training

- A Practical Weekly Template

- Training as Intentional Action

Personal account

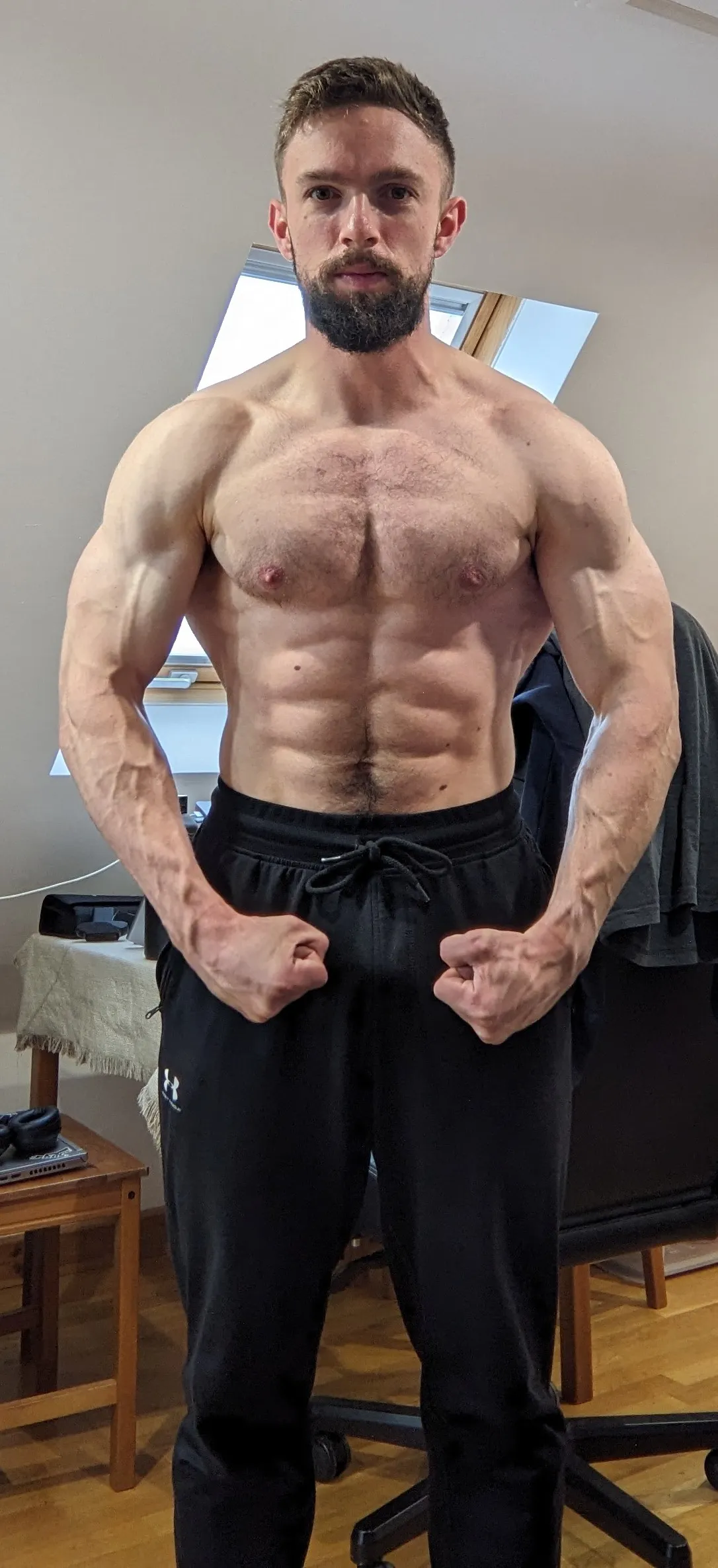

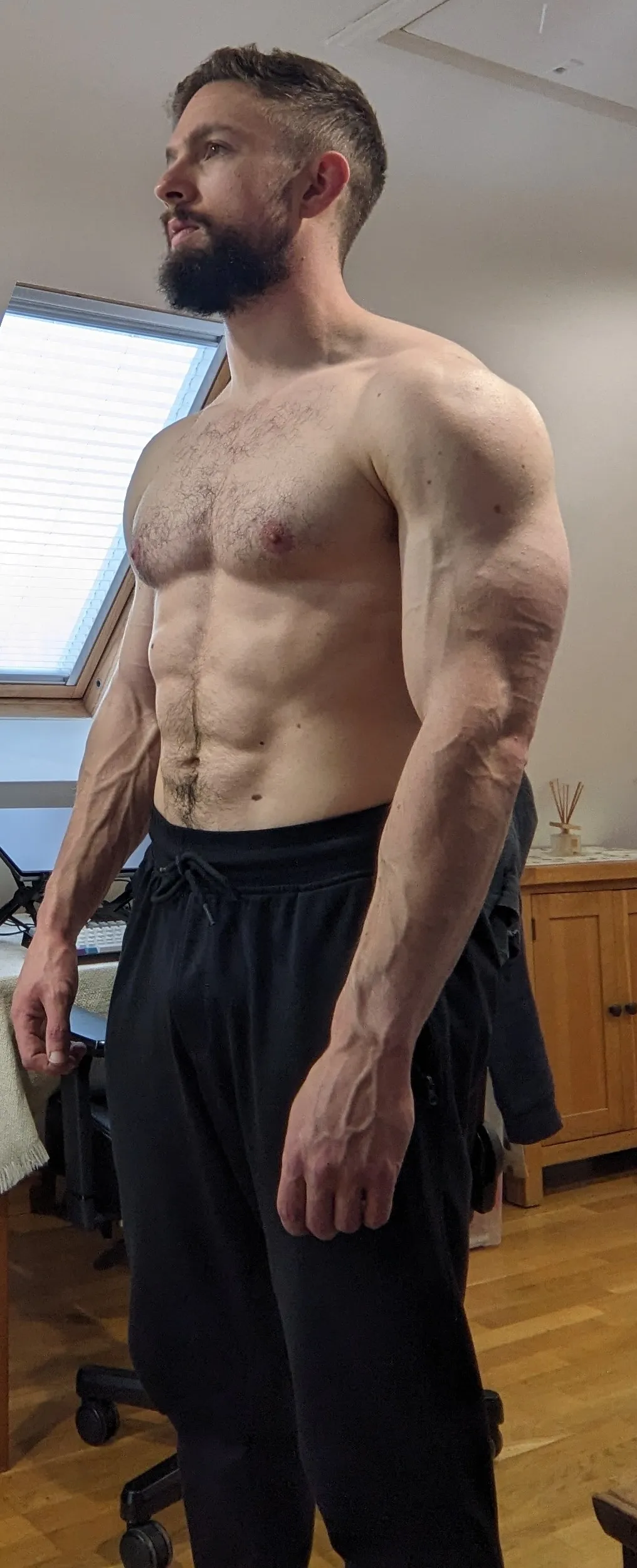

I started out running at school. I was particularly strong when it came to sprinting on the track. Naturally athletic, I’ve always enjoyed competition, exercise and simply getting outdoors in nature. When I started at secondary school, I got into running and progressed in the longer distances, up to half-marathon, taking a lot of inspiration from running videos a stumbled upon on YouTube. This was back in the early 2010s. I ran my first half-marathon in 2012. I have a copyrighted photograph from the local photography company, showing my last few stride before passing over the finishing line on The Hoe in Plymouth, UK. Check it out.

Once I joined University in 2014, this quickly changed. I went from running half-marathons to competing in the sport of Powerlifting. I went from a body weight of around 70kg to around 85kg within a year or so, packing on a good amount of muscle and gaining a lot of strength. Now it’s 2026, and I do both. I love both running and lifting. They bring me a lot of joy and they provide me with a great way to live a high quality of life. In this article, I’d like to share with you how I view exercise today.

|  |

|---|

Even though it’s great that I’ve ran those distances in good times, lifted big weights and built a good physique, for me what matters the most is what I’ve learned about myself in the process that really matters. The physique and fitness is simply a by-product.

Training Without Competing: Exercise as Nervous System Literacy

Most people approach training through two distinct lenses. Sometimes it’s more explicit, through competition - races, leaderboards, personal bests. Other times it’s more implicit, through the endeavour of self-improvement - chasing a future self that is leaner, stronger, calmer, more resiliant and so on. Competition isn’t wrong. It can be clarifying. But it isn’t the only useful way to relate to physical training - and for many people, especially over time, it becomes noisy rather than informative.

The way I choose to think about exercise is not as a contest, but as a practice in attention.

The Nervous System Is Always Listening

Training is often described in terms of muscles, conditioning, or work capacity. These are visible adaptations. They are not the first adaptations that happen.

Every session is filtered through the nervous system. It decides:

- whether the stimulus feels safe or threatening

- whether recovery is permitted

- whether adaptation is sustainable

Mood, sleep quality, baseline stress, emotional tone - these aren’t side effects of training. They are primary outputs of the same system that governs physical change. When training is framed only as effort and progression, the nervous system tends to stay mildly defensive:

- do more

- don’t fall behind

- don’t lose ground

This works, until it doesn’t.

“You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.”

- James Clear

Quality of life erodes not because people train too much (or at all for that matter), but because they train without listening.

From Recognition to Understanding

There’s a difference between:

- hearing and listening

- eating and tasting

- recognising a signal and understanding it

Equivalently, training can sit on either side of that line of attention and intention. Used carelessly, it becomes another source of background stress. Used intentionally, it becomes a way of cultivating self-awareness.

- An easy run might reveal how quickly your mood lifts.

- A heavy set might reveal where unnecessary tension creeps in.

- A restless night after training might reveal a threshold you crossed without noticing.

None of this requires optimisation. It requires presence.

“The quieter you become, the more you are able to hear.”

- Rumi

Exercise as Infrastructure, Not as a Scorecard

When exercise is framed as nervous system hygiene, the questions subtly change.

Instead of:

- Was this hard enough?

- Did I improve?

You start asking:

- Do I feel more grounded afterwards?

- Does this improve my sleep?

- Does this support the rest of my day - or fight it?

This isn’t about avoiding effort. It’s about placing effort downstream of regulation.

Paradoxically, when training supports calm presence, performance often improves anyway - without friction.

The Missing Piece: Parasympathetic Training

Modern life already biases us toward sympathetic dominance: urgency, alerts, constant decision-making. Many training plans unknowingly reinforce this by treating intensity as a moral good.

What’s largely missing is intentional parasympathetic reinforcement.

Short, genuinely easy movement - walking, light running, relaxed lifting - teaches the nervous system something simple and important: effort does not always equal danger.

These sessions don’t build toughness. They build capacity.

“Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.”

- Lao Tzu

A Practical Weekly Template

Below is an example of how this philosophy can be expressed structurally - not as a rule set, but as a scaffold.

Weekly Structure (Example)

| Day | Session Type | Intent |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Parasympathetic micro-run | 15–20 min easy. Calm breathing. Finish feeling better than you started. |

| Tuesday | Optional light movement | Short jog or long walk. Only if energy feels available. |

| Wednesday | Strength | Squat, OHP, pull-ups. Optional 10–12 min easy jog later for sleep quality. |

| Thursday | Parasympathetic micro-run | Same as Monday. No pace targets. |

| Friday | Strength (upper) | Incline DB press, rows, accessories. |

| Saturday | Optional feel-good run | Repeat micro-run or skip entirely. |

| Sunday | Strength (deadlift focus) | No running beforehand. Optional evening walk. |

Total weekly running is modest. The primary goal is regulation. The adaptation is sustainability.

Training as Intentional Action

Seen this way, exercise stops being something you impose on the body and becomes something you do with it.

Like listening instead of waiting to speak. Like tasting instead of consuming. Like understanding instead of merely recognising patterns.

“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.”

- Aristotle

Training becomes less about control and more about cooperation. Less about domination, more about dialogue.

And perhaps the quietest benefit: when movement is no longer a proving ground, it becomes a way of inhabiting your life more fully - calm, attentive, and deliberate.